Hiring an Associate Dentist: Timing & Key Metrics for Success

Part 2: The Right Time

Many practitioners are curious about when to hire an associate dentist to help with the workload. In the first segment of this three-part series, we looked at common reasons doctors consider adding associates, such as capacity issues, a desire to increase profitability, and exiting the profession. In this segment, we will investigate how to evaluate specific office metrics to determine if the timing is right for hiring an associate dentist.

Opinions differ about what metrics indicate readiness for adding a new associate dentist. Most experts distill the discussion around the number of active patients, current profitability, and resources. Below, we will briefly examine these elements.

Number of Active Patients

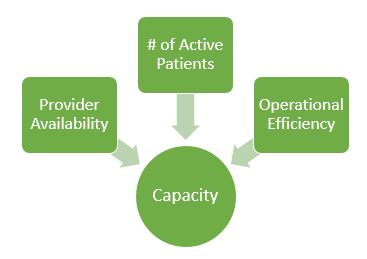

In our first segment, we discussed capacity in two dimensions: operational and doctor capacity. Capacity refers to the ability of patients to be seen within 3 weeks of requesting an appointment. Capacity is related to the number of active patients in the practice, the provider’s availability, and the office’s operational efficiency. Assuming the office’s operations are excellent and the doctor’s availability is at the preferred level of the individual provider, it is advisable to evaluate the number of active patients in the practice.

The number of active patients is the total of individuals seen in the office for treatment within the last 18-24 months. Patients of record who have not visited the office in more than two years are not contributing to capacity problems, so they should not be considered in determining the need for an associate. Experts suggest that a single dentist can only care for 1,000-2,000 patients.

Gonzalez (2017) suggests that in addition to 2,000 active patients, general dentists should expand when the hygienists are booked 4-6 weeks in advance and there are sufficient financial resources to pay the associate’s salary for 6-12 months. Malcmacher (2005) states that doctors should aim to consistently add 10-25 new patients to the practice per month. Kesner (2018) recommends a higher standard of 35-40 new patients each month. New patient additions below that threshold may endanger office profitability if a new associate is on the team. Kesner (2018) reminds doctors seeking to add an associate that they should be experiencing a case acceptance rate of 80%. Dentists with low case acceptance rates may experience lower profitability. Before proceeding with the associateship, work on operations to improve acceptance rates. Also, Kesner (2018) notes that patient referral rates of 40%-50% indicate that the practice attracts and maintains patients.

Additionally, dental offices lose about 10% of their patients annually, so doctors should carefully watch the patient attrition rate over several months to evaluate their office trend before jumping into an associateship (Remi, 2023). Remember, it will take 18-24 months for patient attrition to manifest in the active patient pool. It is crucial to keep in mind that these are only general guidelines. Each practitioner must decide for themselves what indices best represent their practice.

Current Profitability

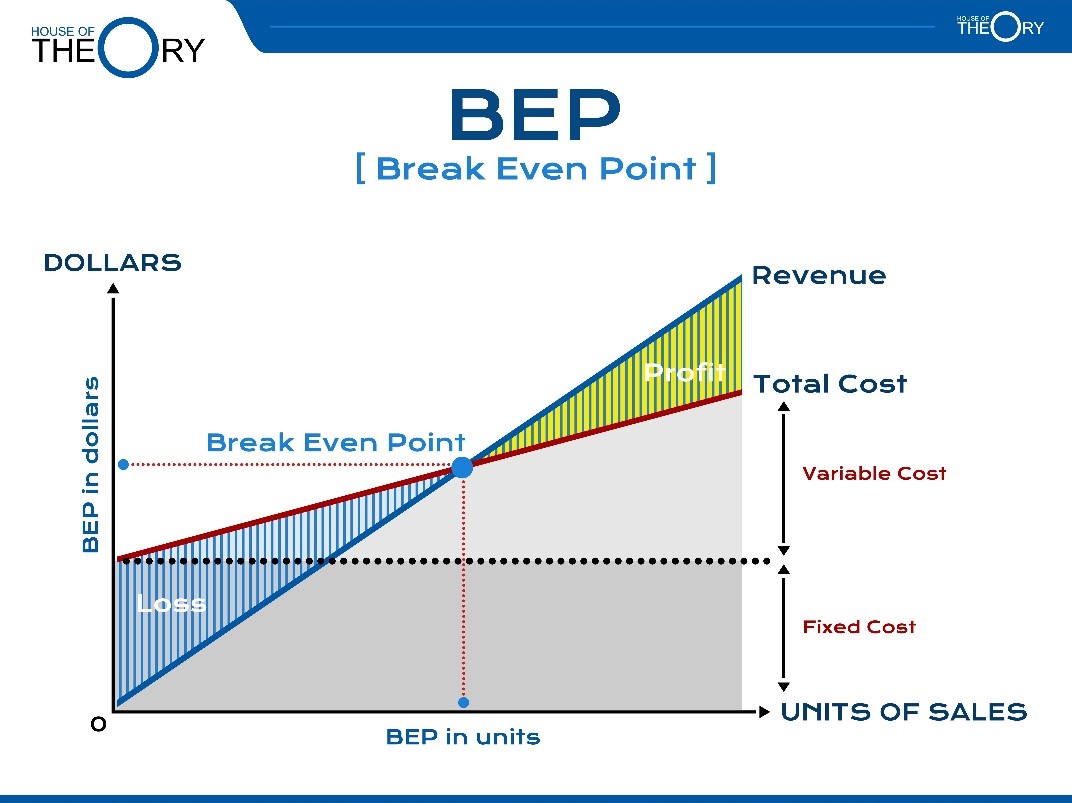

Measuring an office’s profitability is a complex affair. Associates working in offices not ready to transition owners will be an expense to the owner. However, associateships leading to a buy-out can be structured differently. In their Practice Transition Toolkit, Cain Watters & Associates (n.d.) suggest that one consideration of adding an associate in transition strategies is the ability to eventually share fixed costs between parties. Fixed costs are not affected by how many providers there are in the practice. These costs include rent, insurance, professional fees, and subscriptions. In contrast, variable costs (direct costs) are those that are a result of production. Variable costs include clinical supplies, laboratory bills, and staffing costs. For example, the rent doesn’t change if you add an associate, and your monthly subscriptions remain static. However, laboratory and supply bills will increase with an associate in the practice. If the practice grows, the fixed costs become a smaller percentage of the expenses while profits rise. The direct costs are shared proportionally, which leaves the owner dentist with more profit. Let’s look at an example of an associateship without a buy-out option.

Another financial consideration when contemplating adding an associate is for the owner to calculate their current break-even point. The break-even point gauges your ability to add an associate because it lets you know how much profit is needed to maintain your financial obligations and goals. The break-even point is calculated by the following formula:

Break-Even = Monthly Costs/Gross Profit %

Monthly costs are comprised of three elements:

- Fixed costs (rent, debt service, insurance)

- Owner’s Expenses (lifestyle, taxes, profit sharing, saving)

- Variable Costs (supplies, laboratory, salaries)

Gross profit percent is calculated using this formula:

Gross Profit % = 100% – Total Variable Cost %

Using our example above and assuming monthly owner expenses as $25,000, the monthly break-even point would be calculated as follows:

Fixed Costs: $16,333

Owner’s Expenses: $25,000

Variable Costs: $392.000 (total variable costs ) ÷ $980,000 (total collections) = .40 (40%)

Gross Profit Percent: 100%- 40% = .60

Break Even = ($16,333 + $25,000) / .60 = $68,888/month or $826,656/year

Since the practice’s collections are $980,000, the owner may have enough profitability to introduce an associate into the practice because there is sufficient discretionary profit (Cain Watters & Associates, n.d.). Out of control variable costs coupled with poor collections and high fixed costs may be indicators that the timing is not right to add a provider and that the owner should look for problems in the office’s operations or overhead.

The graph below illustrates how the break-even point is the pivot between profit and loss and how variable and fixed costs relate to this financial indicator. Knowing your office’s break-even point helps you keep an eye on profitability.

Are your Resources Sufficient?

A further consideration for owners wishing to add an associate is determining if they have the necessary space, equipment, and staff to add a new dentist successfully. If space is a concern, Kesner (2018) suggests increasing the office’s operating hours from 8 hours each day to 12 per day. Doing this allows each doctor to work a six-hour shift. If both doctors can work simultaneously, ensure there is enough equipment and supplies to treat the extra patients.

Staffing is another concern to address in associateships. Be sure to carefully evaluate which auxiliary personnel and hygienists will be assigned to the new doctor. If your current staff is not sufficient, be sure to include the costs of hiring new staff members in your break-even point calculation.

Summary

Once you determine you need to add an associate, it is important to take time to consider if the timing is appropriate. Consider the office’s patient characteristics, profitability, and available space as factors to help you gauge if the timing is reasonable. Evaluating these factors before the decision is made will help ensure that your associateship will enrich your practice experience.

Resources:

Cain Watters & Associates. (n.d.). Practice transition toolkit. Financial Planning Resources (cainwatters.com)

Gonzalez, S. (12 June 2017). How to know if your dental practice can add an associate | Dentistry IQ.

Kesner, M. (2 May 2018). How to decide when to hire an associate | Dental Economics.

Malcmacher, L. (1 Aug 2005). The new patient myth | Dental Economics.

Remi. (23 Feb 2023). How Profitable are Dental Practices? Break-even & Profits (sharpsheets.io)